The ACLU of Maine works on a variety of issues in the Maine State Legislature to protect and expand the civil rights and liberties of all people in the Pine Tree State. All of our work is done through a racial justice lens.

Our nation's political system was designed to uphold white supremacy and built on the oppression of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people. We must dismantle the systems and policies that continue to uphold white supremacy and seek justice for past harms. Our team works closely with grassroots organizations and groups throughout Maine so the policies we promote at the State House reflect the realities of the people they will affect.

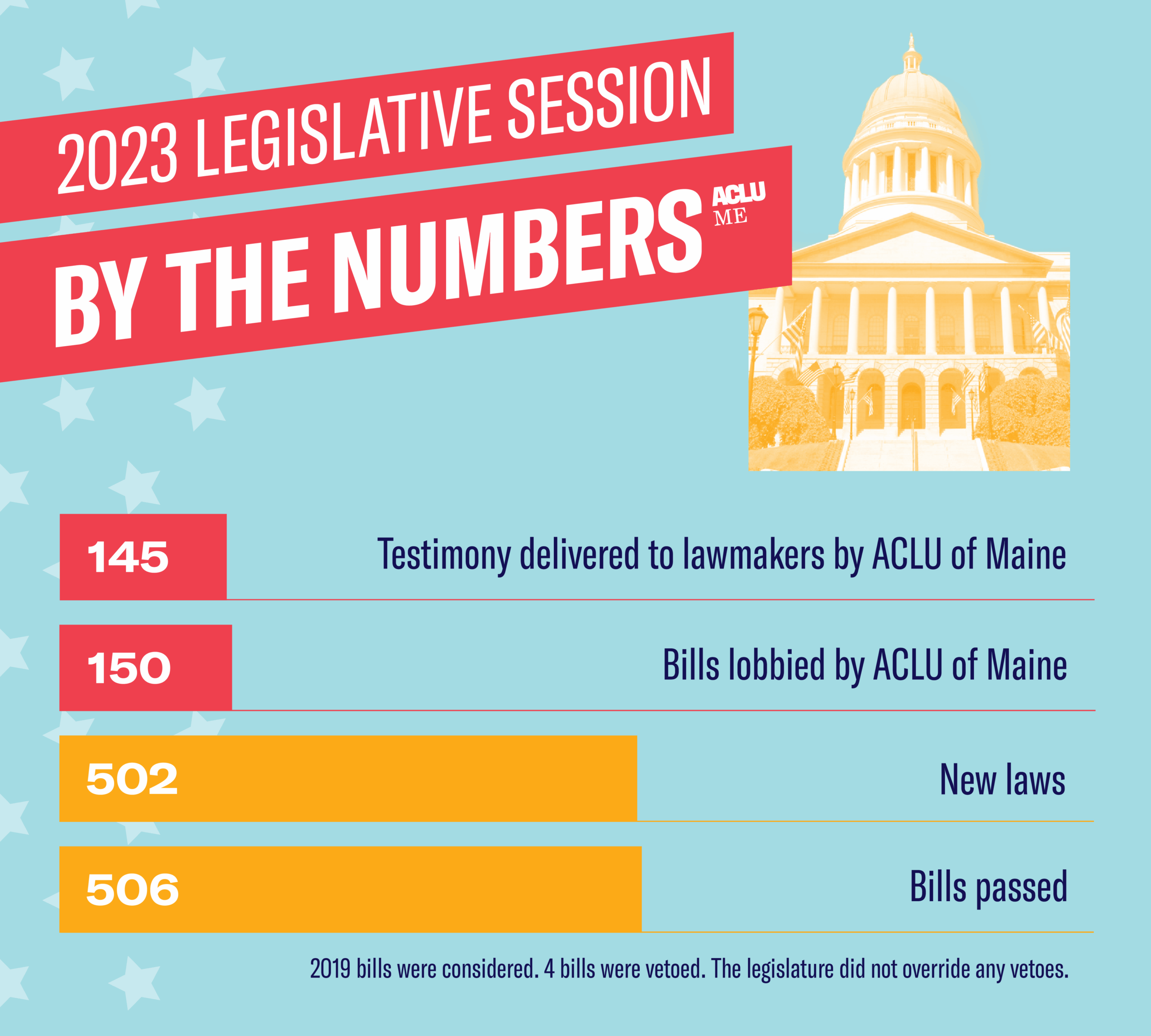

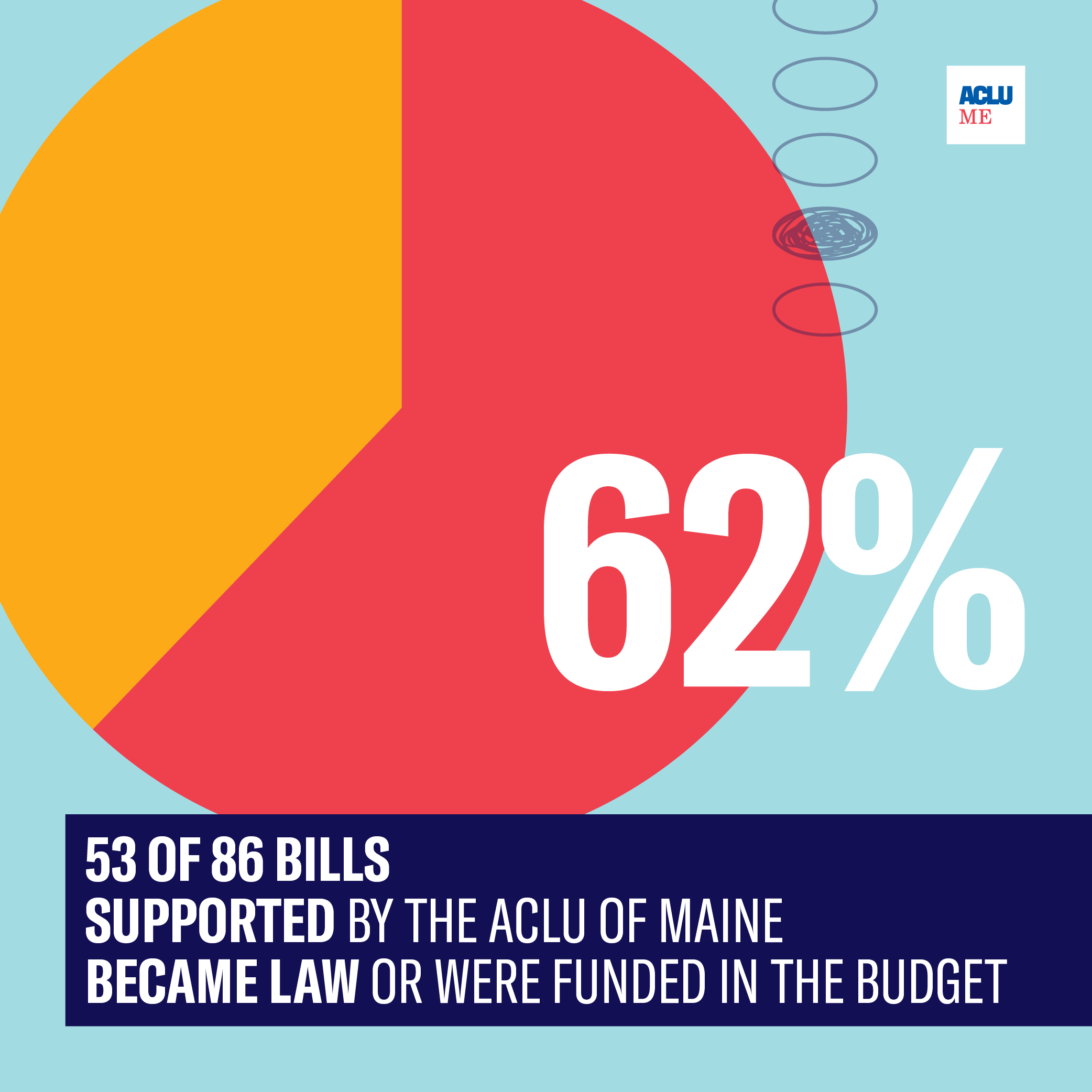

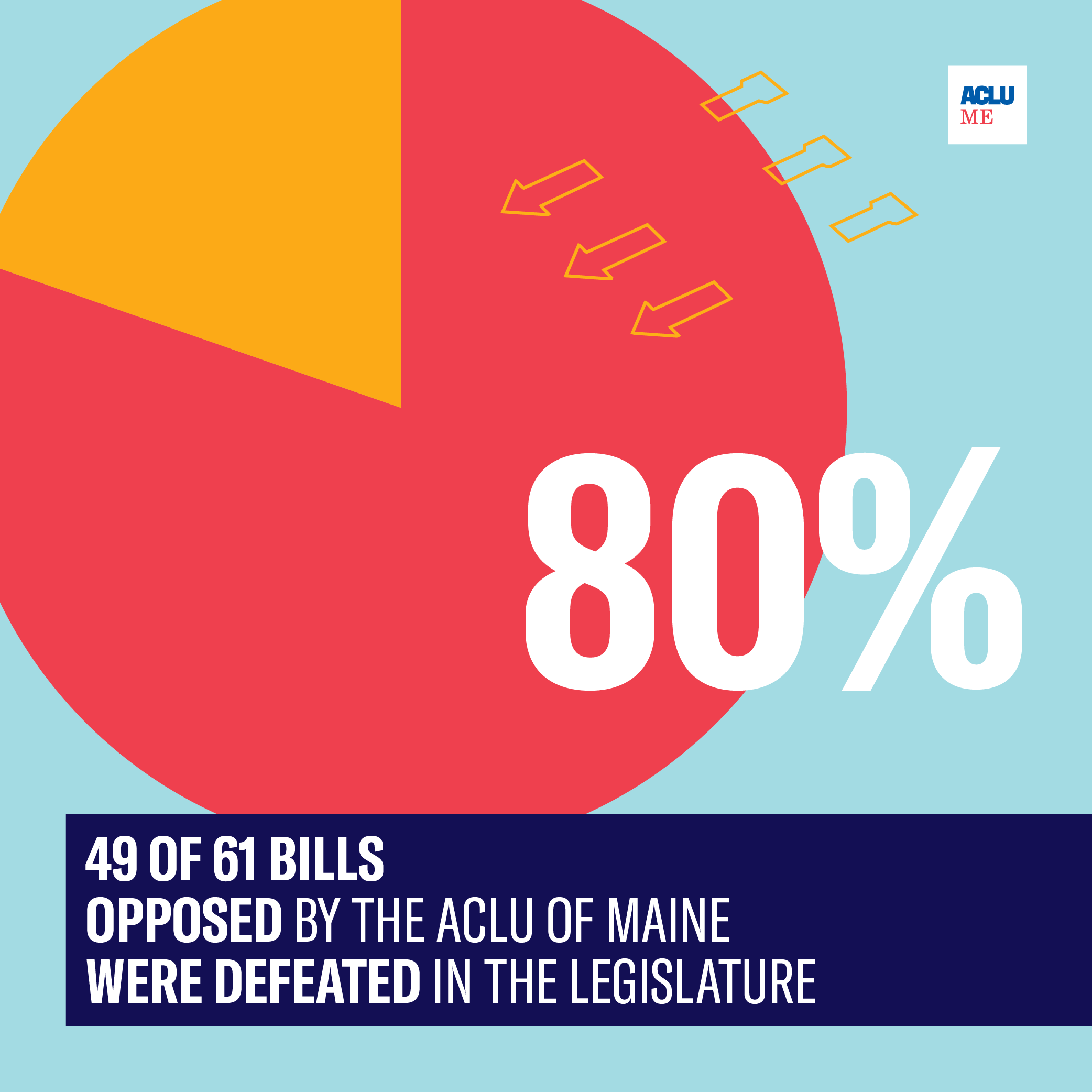

|

|

|

|

LEGISLATIVE VICTORIES

Alongside our allies, members, and other advocates, the ACLU of Maine won a number of victories during the 2023 legislative session, from expanding abortion access to protecting criminal legal reforms. The 2023 session ran from December 7, 2022, through July 26, 2023. Bills referenced throughout this update are referred to as "LD," the abbreviation for "Legislative Document."

REPRODUCTIVE FREEDOM

Against a landscape of increasing attacks on sexual and reproductive healthcare nationwide, the Maine legislature passed several new laws that protect and expand access to abortion and related care. Key bills that became law this year include:

Reproductive freedom means all people have the rights and access to resources to make the best decisions for themselves, whether that means continuing a pregnancy or seeking abortion care.

- Removing politicians from decisions about abortion: LD 1619 protects and expands abortion access by allowing people to seek care when medically necessary – without political interference. LD 1619 removed Maine’s black-and-white cutoff for receiving abortion care, leaving these important decisions to patients and their doctors.

- Protecting Maine providers: Extreme anti-abortion politicians will not stop at their own state borders in their effort to ban abortion in all 50 states. LD 616 protects abortion providers in Maine from retaliation from out of state actors.

- Protecting abortion access in all Maine towns: LD 1343 prohibits Maine towns, cities, and other municipalities from banning abortion at the local level.

- Covering abortion care: LD 935 ensures no person with health insurance in Maine has to pay out-of-pocket for abortion care.

- Maintaining care despite hospital mergers: LD 263 protects access to sexual and reproductive healthcare, including abortion care, in the event of a hospital merger with a religiously affiliated organization.

- Increasing access to paid family leave: Maine’s state budget includes funding to allow up to 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave. Women and women of color are disproportionately pushed out of the workplace and lose earning potential without paid leave. No person should ever be forced to choose between a paycheck and caring for their family.

ENDING THE WAR ON DRUGS

We defeated several attempts to double down on the failed and racist policies of the War on Drugs alongside other Maine advocates. Lawmakers must focus on root causes of problematic drug use: poor access to health care, housing, jobs, and education. Incarceration will never solve a public health crisis.

LDs 828, 1295, and 1509 would have increased criminal penalties for people living with substance use disorders. These bills doubled down on the core ideas of the failed War on Drugs by attempting to punish people out of drug use instead of giving them the support they need to lead healthier lives.

Additionally, a bipartisan majority defeated LD 1087, a bill to roll back a ban on most no-knock warrants, like the one that led to Breonna Taylor's murder. No-knock warrants are a staple of the failed War on Drugs that disproportionately terrorize Black, Indigenous, and immigrant communities. These deadly raids endanger both civilians and law enforcement, and they have no place in Maine.

CRIMINAL LEGAL REFORM

The ACLU of Maine seeks to end mass incarceration and our state’s reliance on police and prisons to address social issues. Policies that support mass incarceration target and disproportionately trap people of color, particularly Black people, and people with low incomes, in the revolving door of the criminal legal system. With so-called tough on crime politics making a comeback in recent years, many important reforms to the criminal legal system were under threat during the 2023 session.

We convinced lawmakers to uphold important bail reforms they passed in 2021 by defeating LD 1299. The 2021 law, written and championed by the ACLU of Maine and now Speaker of the House Rachel Talbot Ross, eliminated cash bail for most class E crimes, the state’s lowest level offense. A person's freedom should never depend on their wealth.

LGBTQ EQUALITY

Alongside our partners and following the lead of Maine’s LGBTQ advocacy organizations, we helped reinforce that Maine is a place where trans and non-binary belong.

LD 535 has expanded access to gender-affirming care for 16- and 17-year-olds. LD 1040 enshrined MaineCare’s coverage of gender-affirming care into law. Before this law, coverage was available under the Maine Department of Health and Human Services’ rules, but could have been easily revoked by a future governor. This life-saving care is essential to protecting bodily autonomy and a person’s right to make the best decisions for themselves.

Additionally, LD 942 became law, providing a third gender option on all state forms. Maine already had this for some government documents, such as state IDs, but other government documents still left non-binary people without accurate, inclusive documentation of their gender identities.

STOPPING CLASSROOM CENSORSHIP

Like many states throughout the nation, Maine was hit with bills to censor and limit access to books in public schools. Following robust engagement from the ACLU of Maine, LGBTQ rights organizations, educators, librarians, and more, lawmakers defeated these dangerous proposals.

Bills like LDs 123, 1008, and 618 would have restricted access to or banned books and censored conversations about race and sexuality. Bills like this are an attempt to whitewash history and erase the stories of marginalized communities, particularly LGBTQ people and people of color. Students have a First Amendment right to not only speak freely but to freely access information, and that includes books.

Read more about our work fighting book bans in Maine and know your rights at school.

LOOKING AHEAD TO 2024

Several pieces of priority legislation will be carried over to the next legislative session. We look forward to engaging lawmakers to get these bills across the finish line in 2024. Four key legislative priorities include guaranteeing protecting Mainers' privacy from Big Tech, giving teachers the necessary resources to teach Wabanaki Studies, enforcing the right to a speedy trial, and implementing a public health response to problematic substance use.

PROTECTING MAINERS FROM BIG TECH

Private companies are currently free to exploit our personal data to track movements and profit from our most personal information. Privacy isn’t about secrecy. It’s about control. Without sensible guardrails around these abusive practices, governments, individuals, and companies will continue to have the ability to purchase information that could be used to track us at protests, places of worship, family planning clinics, and more.

WABANAKI STUDIES

22 years ago, Maine passed a visionary law mandating public schools teach students about the Wabanaki Nations, but the law has not been effectively implemented. We will continue advocating for educators to receive the necessary support and resources to teach students about Wabanaki Nations’ culture, government, economic systems, and relationships with the State of Maine.

Many students have been left with no knowledge about the Wabanaki, including that they still exist. As a state and country, we must acknowledge and learn about our full past and present so we can make informed decisions about our future. This includes the colonization that led to the creation of the State of Maine, and the genocide, oppression, and attempted erasure of the Wabanaki. Wabanaki citizens continue to face longstanding political, social, and economic oppression from our state and federal governments. Ensuring students are taught about them is one way to tackle these problems.

Read more about Wabanaki Studies and the implementation of the 2001 law in our report co-authored by the ACLU of Maine, Wabanaki Alliance, Abbe Museum, and Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission here.

ENFORCING THE RIGHT TO A SPEEDY TRIAL

When the government chooses to charge a person with a crime, it is the government’s responsibility to provide a fair legal process, including a speedy trial. Maine should join 41 other states and the federal government by implementing specific timelines to ensure criminal cases proceed fairly and efficiently. Currently, people are waiting years for their day in court, even on misdemeanor cases. Without action, Maine will continue failing to uphold people’s constitutional rights and court backlogs will continue to grow at ever increasing expense to taxpayers.

ADDRESSING MAINE’S DEADLY OVERDOSE CRISIS THROUGH PUBLIC HEALTH MEASURES

Incarceration will never be the answer to social problems, including Maine's deadly overdose crisis. Too many people in Maine who want treatment for a substance use disorder cannot get the help they need, and instead are surveilled and punished for their health condition. We must increase pathways to help so people in all parts of the state can get the support they need to thrive on their own terms. Maine families are desperate for our leaders to take a new approach – and lives depend on it. Investing in a public health response to substance use will open doors to treatment, keep communities whole, and save money in the long run.

Read more about the true cost of the failed War on Drugs and a better path for Maine in our report co-authored by the ACLU of Maine and Maine Center for Economic Policy here.

SUPPORTING OTHER ADVOCATES

The ACLU of Maine is also looking forward to supporting other organizations and advocates taking the lead in other fights for civil rights and liberties at the State House, from protecting our democracy to upholding workers' rights.

Ending Jim Crow-era labor laws:

Immigrants' rights and fair labor advocates led the charge for LD 398 during the 2023 session. LD 398 would have reduced racial inequities in Maine and improved our state’s economy by extending some basic workplace protections to farmworkers – such as the minimum wage. Farm workers are disproportionately workers of color and have long been excluded from improved labor standards dating back to the New Deal. The exclusion of farm workers from fair labor laws is a deliberate wrong that is rooted in the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow.

These frontline workers endure tremendous hardships to support Maine’s economy, and they deserve the same workplace standards and protections as all other workers. The measure passed both chambers, but was vetoed by Governor Mills. We will continue supporting similar legislation to advance racial justice in Maine and give the workers that sustain some of our vital industries the resources to support themselves, their families, and their local economies.

Restoring tribal sovereignty:

The Wabanaki were the first on this land now called Maine, and the Wabanaki citizens deserve the right to self-determination on this land they never ceded. LD 2004 would have granted the Wabanaki Nations some of the federal benefits afforded to every single other federally recognized tribe in the United States, moving them closer to being on the same footing as all other federally recognized tribes. Tribal governments have proven for decades that when granted these federal benefits, they serve all communities, as outlined in a 2022 analysis by the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development. When the Wabanaki prosper, all of Maine prospers.

A bipartisan majority passed LD 2004, but the measure was vetoed by Governor Janet Mills. We will continue supporting Wabanaki leaders in their fight for sovereignty.

Protecting democracy by ensuring the candidates with the most votes win:

Imagine a system to elect the President of the United States where the candidate with the most votes could actually lose. You just imagined our system. And it has happened more than once — and as recently as 2000 and 2016, despite the fact that George W. Bush and Donald Trump received fewer votes than their opponents.

Under National Popular Vote, the candidate with the most votes in the country would win — not most of the time, but every time. We will continue supporting voting rights advocates as they lead the effort for Maine to join the National Popular Vote Compact. Under this proposal, states would give their electoral votes to the candidate for president who gets the most votes in the country. National Popular Vote ensures that each vote cast has an equal impact on the outcome of the Presidential election, thus furthering the principle of one person, one vote.

Currently, the 16 states that have joined the compact hold a collective 205 electoral votes. Once enough states join that they hold 270 electoral votes (the number needed to win the Electoral College), the candidate with the most votes nationwide would win the election. Read more about it here.

Closing Maine's youth detention center:

Maine's young people need access to support services like after-school programs, counselors, therapy, and violence intervention. All kids make mistakes and misbehave, and incarceration will never be the right response. Youth incarceration disproportionately entangles children of color – particularly Black children – and children with disabilities in the criminal legal system.

Children in Maine's Long Creek Youth Development Center have faced violence from guards, had their civil rights violated under the American with Disabilities Act, and are separated from their families and communities. We will continue supporting legislation to close Long Creek, and instead invest in the support services that children and their families need to thrive.

Increasing access to affordable housing:

Historic and ongoing segregation and discrimination has prevented marginalized groups — particularly Black communities — from accessing safe, affordable housing and home ownership. A lack of access to housing is the upstream cause of the downstream crisis for unhoused people. One statistic tells a lot of the story: every $100 increase in median rent is associated with a 9 percent increase in the homelessness rate. Read more about why the housing crisis is a civil rights crisis here.