The Good Samaritan law was designed to save lives – and it has. But Maine's highest court recently ruled that a person's arbitrary word choice during an emergency should mark the difference between prosecution and freedom.

In mid-January, Maine’s highest court issued a decision in Maine v. Beaulieu. It was the court’s first case on the latest version of our Good Samaritan law, a measure designed to save lives in the midst of the ongoing overdose epidemic.

The law was first passed in 2019, and then strengthened in 2022. At its core, Maine’s Good Samaritan law was designed to save lives. The opioid crisis – created and driven by corporate greed, lax government oversight, and amoral business practices – has devastated many lives and communities in Maine and throughout the country. The problem is so widespread that nearly one-third of adults know someone who has died from an overdose.

What is a "Good Samaritan” law?

Opioid overdoses can often be reversed if a person receives emergency medical attention in time. Unfortunately, people are often afraid to call 911 because they don’t want their friends or themselves to be arrested. The Maine legislature recognized that saving a life is more important than punishing someone for a low-level drug offense.

In 2019, lawmakers passed a bill to ensure people knew they could seek emergency medical services without fear. The law protects people from prosecution for certain crimes when they seek emergency services for a drug overdose, render aid at the scene of an overdose, or experience an overdose themselves.

The Underlying Story

On a summer evening in 2022, a woman was driving north on I-295. She took the Brunswick exit and “noticed a vehicle parked a little sideways on the left shoulder, which [she] thought was a little odd.” She continued her journey. Upon returning two hours later, she saw the car again parked in the same place. “[V]ery worried the driver was [having] or had a medical event," she went to the Brunswick Police Station and told officers what she saw.

A police officer arrived at the parked car and noticed “a man in wet clothes who was slumped over in the driver’s seat of the vehicle...” When the officer reached into the car to wake the man, the man sat up with “a long glob of drool...hanging from his mouth.” The officer reported the man had small pupils, droopy eyelids, and heavily slurred speech. The officer stated he believed all of this to be “consistent with drug use.” The man, well enough to talk, told the police his name was Billy Beaulieu.

Mr. Beaulieu told the police that he had taken Suboxone and gabapentin earlier that day. After he failed several field sobriety tests, the police arrested Mr. Beaulieu and took him to the station. He was soon released on bail. About two months later, the state charged Mr. Beaulieu with one count of criminal OUI (Class C), a crime punishable by up to five years' imprisonment and a fine of up to $5,000.

The Immunity Claim

At trial, Mr. Beaulieu argued that he was immune from prosecution under the Good Samaritan law. To support his argument, Mr. Beaulieu submitted the witness statement written by the woman who saw him on the side of the road. The trial judge denied Mr. Beaulieu’s motion, finding that the police didn’t arrest Mr. Beaulieu “in response to a call for assistance for a suspected drug-related overdose.” Instead, the judge found that the officer “went there to the scene because of [the woman’s] concern that he had a medical event.”

In other words, the Good Samaritan law only applies when a caller suspects a drug-related overdose, not when the caller is concerned about a medical event. An arbitrary and probably hasty choice of words from a concerned passerby determined if Mr. Beaulieu would be charged. Mr. Beaulieu appealed to the Law Court.

The Law Court’s Analysis

In its analysis, the Law Court focused on the first paragraph of the Good Samaritan law. That section states the law applies “[w]hen a medical professional or law enforcement officer has been dispatched to the location of a medical emergency in response to a call for assistance for a suspected drug-related overdose.”

Like the trial court, the Law Court latched onto the distinction between a “medical event” and “assistance for a suspect drug-related overdose.” The court decided the woman who sought help suspected a “medical event” and not a “drug overdose,” so the Good Samaritan law did not apply. To trigger the Good Samaritan law, the woman must have suspected a drug overdose, and “[n]o reasonable interpretation of 'medical event’ supports [the] argument that it necessarily refers to a drug overdose.”

Implications for Harm Reduction, Mass Incarceration

The Beaulieu decision does not explicitly require the caller to use certain magic words for the situation to fall under the Good Samaritan law, but it requires "the caller must suspect that a drug-related overdose has occurred." In other words, what seems to matter is the caller’s belief — specifically, that the caller believes they are witnessing an overdose.

Under Beaulieu, people must suggest they believe an overdose is happening to be protected under the Good Samaritan law. This might look something like a person saying, "I suspect that a drug-related overdose has occurred.” (To be sure, the opinion's footnote eight says that "[requiring] precise wording would produce absurd results.")

All we know for sure from the Beaulieu decision is that, in this case, the phrase "medical event" was too broad to support the inference that the caller suspected an overdose. If the caller had said something like, "I think this man is overdosing," the outcome might have been different.

Witnessing a potentially deadly drug overdose can be extremely stressful, and most people are not intimately familiar with the intricacies and nuances of every state law. It is unwise, unfair, and unsafe to expect or require people in that situation to be able to rationally assess whether they are saying the right words or phrases. The greatest concern of a person in this situation should be how they can most quickly get help and save a life – not if they are using the right phrasing to be protected under the law.

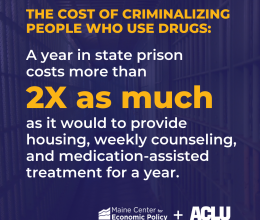

Additionally, by limiting the effectiveness of the Good Samaritan law, this decision will continue prosecutions for substance use. Problematic substance use is a health condition that must be addressed with a public health response – not punishment and incarceration. We all deserve to live in safe and healthy communities, but punishing people for a health condition is not the answer. We must address the root causes of issues like substance use by implementing evidence-based solutions that give people the resources they need to thrive on their own terms: affordable access to health care, housing, education, and job training.

How to be a Good Samaritan Following Beaulieu

In a curious footnote, the Beaulieu decision says, “the legislative record reveals a purpose of the statute more focused than simply saving lives.” Instead of “simply saving lives,” the Law Court found, “floor debates of the...bill...demonstrate that the statutory immunity was intended to incentivize individuals in 'drug-using communities' – who are 'on the scene’ of a drug overdose – to call 9-1-1 without fear of prosecution.”

But Senator Chloe Maxmin, the bill’s sponsor, said in her testimony that the “pure intent of this bill is to save Maine lives.” This was Mr. Beaulieu’s understanding of the statute, too, and that’s what he argued at trial. Indeed, it’s what members of the recovery community and the bill’s authors believed when they persuaded legislators in Augusta to support the bill in 2022.

Beaulieu means that for our Good Samaritan law to be effective, those who call for help must suspect a drug-related overdose – not some other or broader category of crisis. Otherwise, a call for help could become a call for prosecution.